Labour lost their special votes advantage

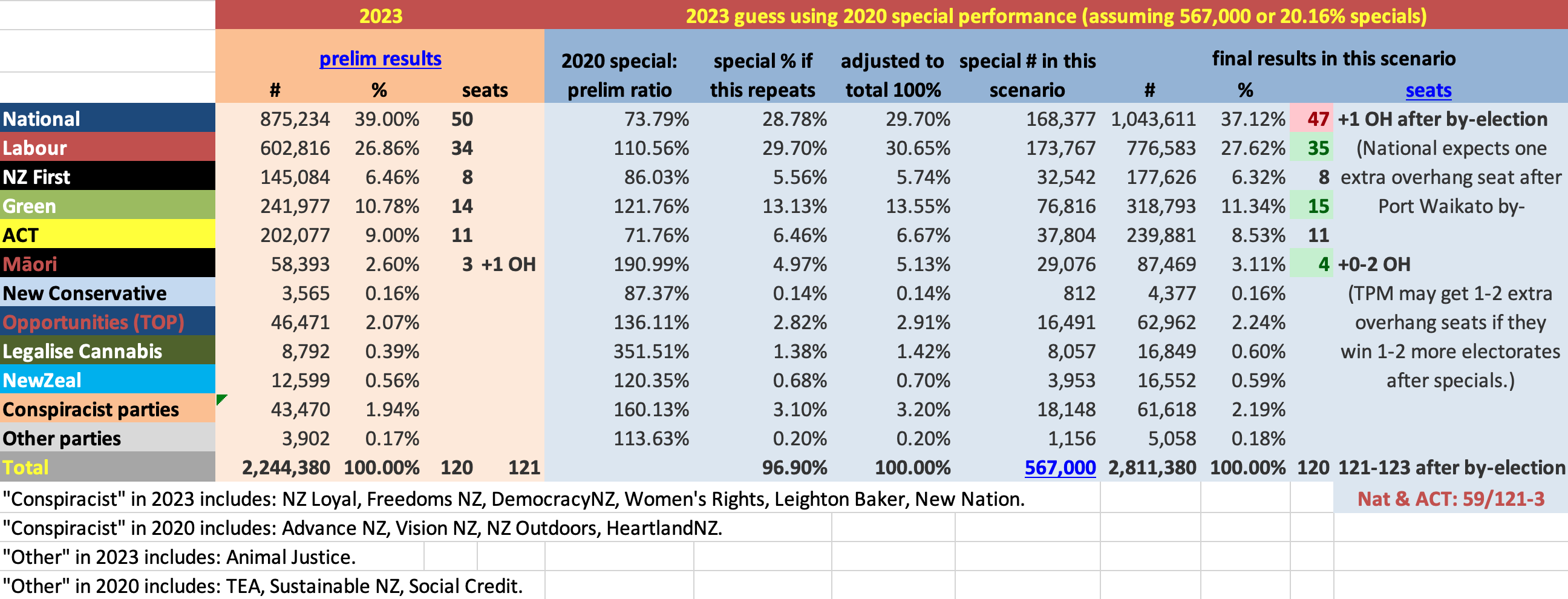

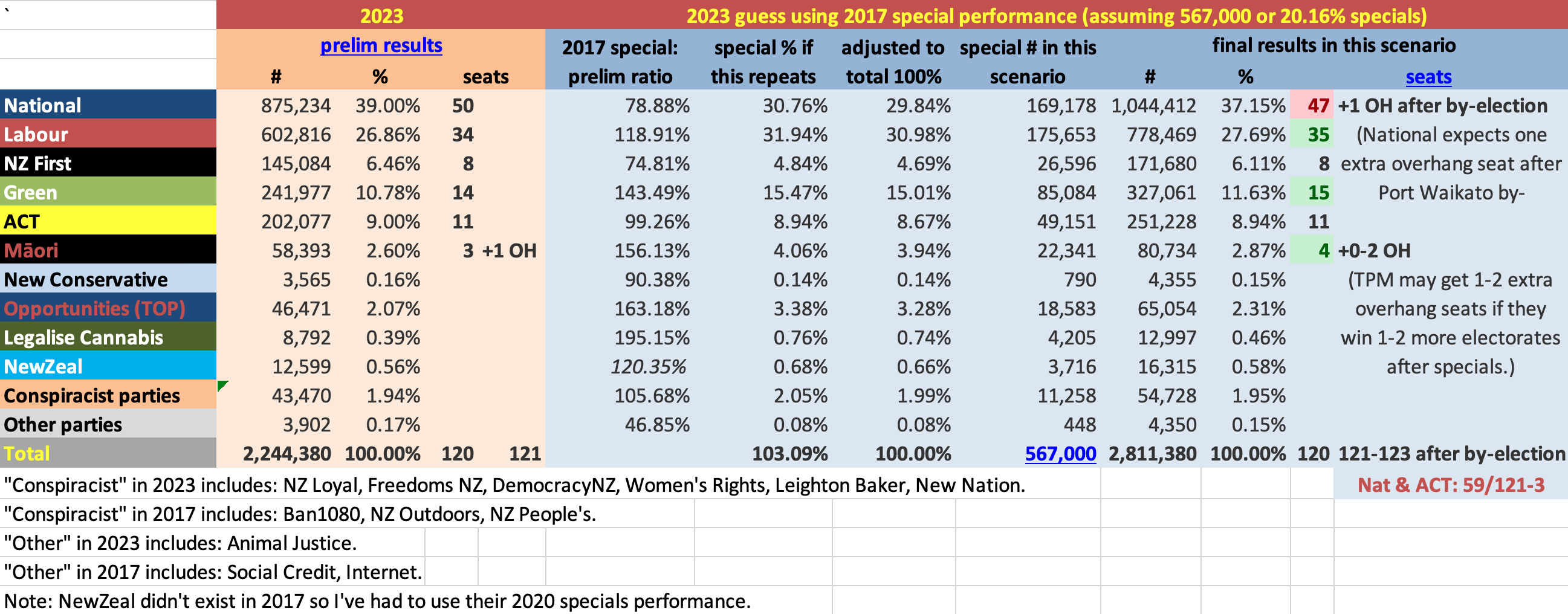

The final NZ election results are out, and my idle spreadsheet-fuelled predictions are proven partly but notably not entirely correct. Most significantly, Labour almost entirely lost their special votes advantage. Since 2005, Labour had always increased their vote when the final results including specials were unveiled, and actually they’d been getting better and better on specials, peaking in 2017. This year Labour did almost exactly the same on specials as on preliminary votes. So this was the worst they’d done on specials since 2002.

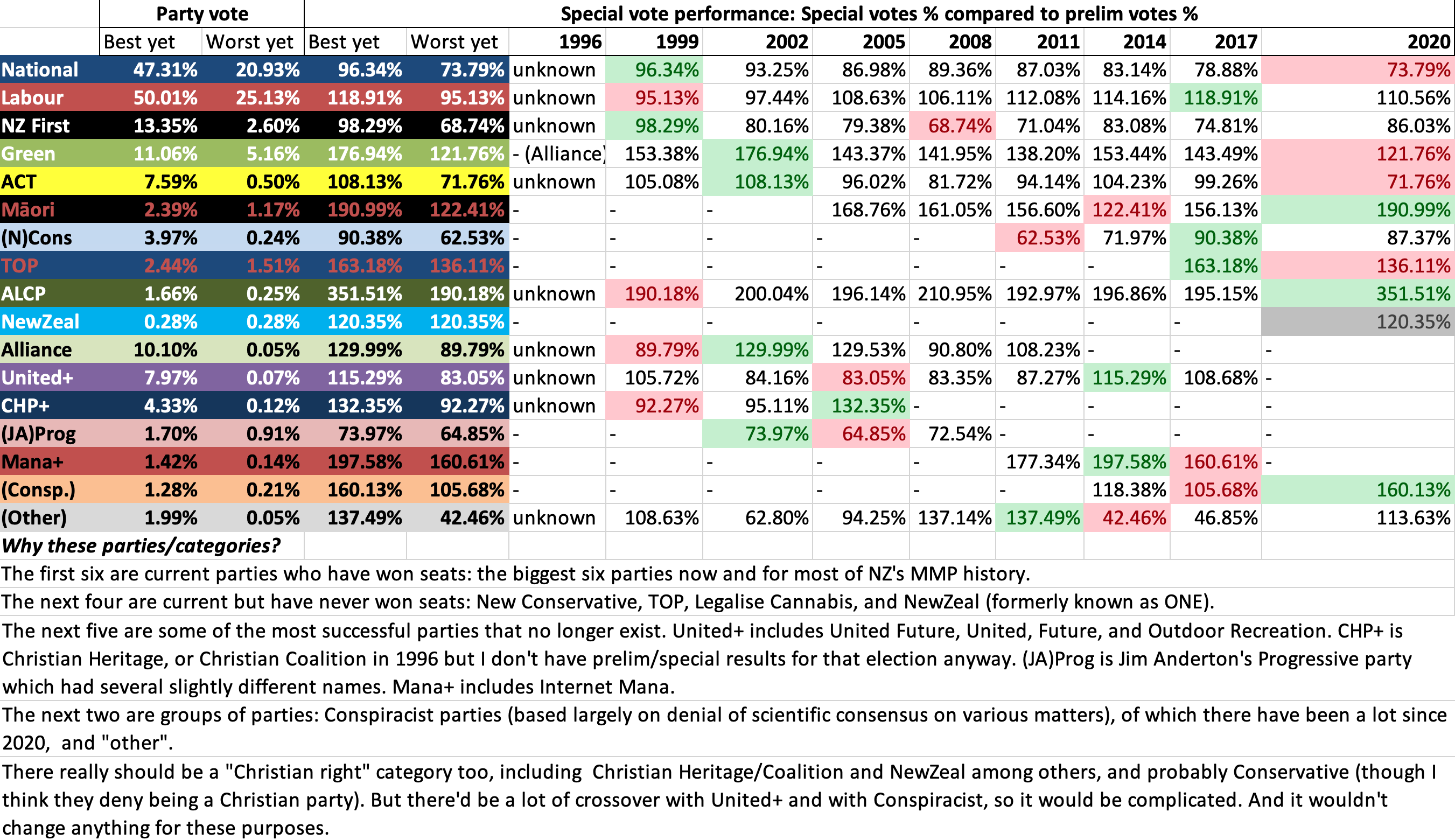

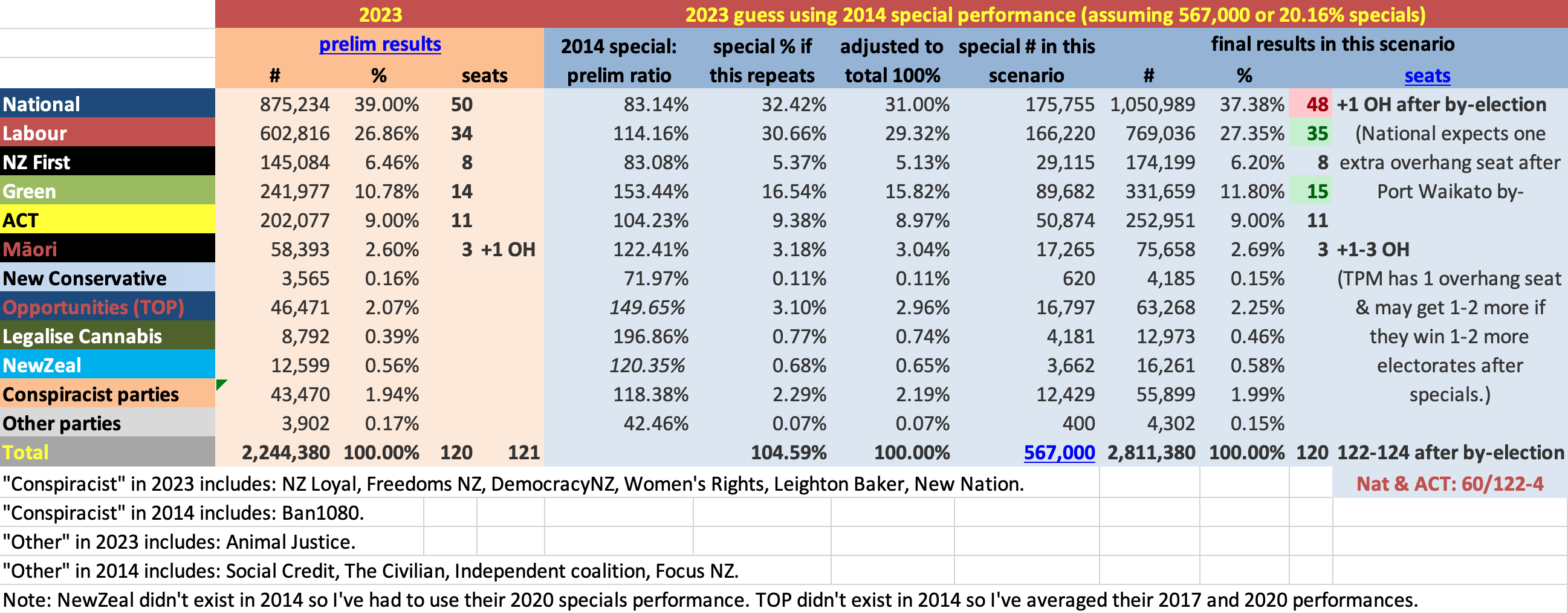

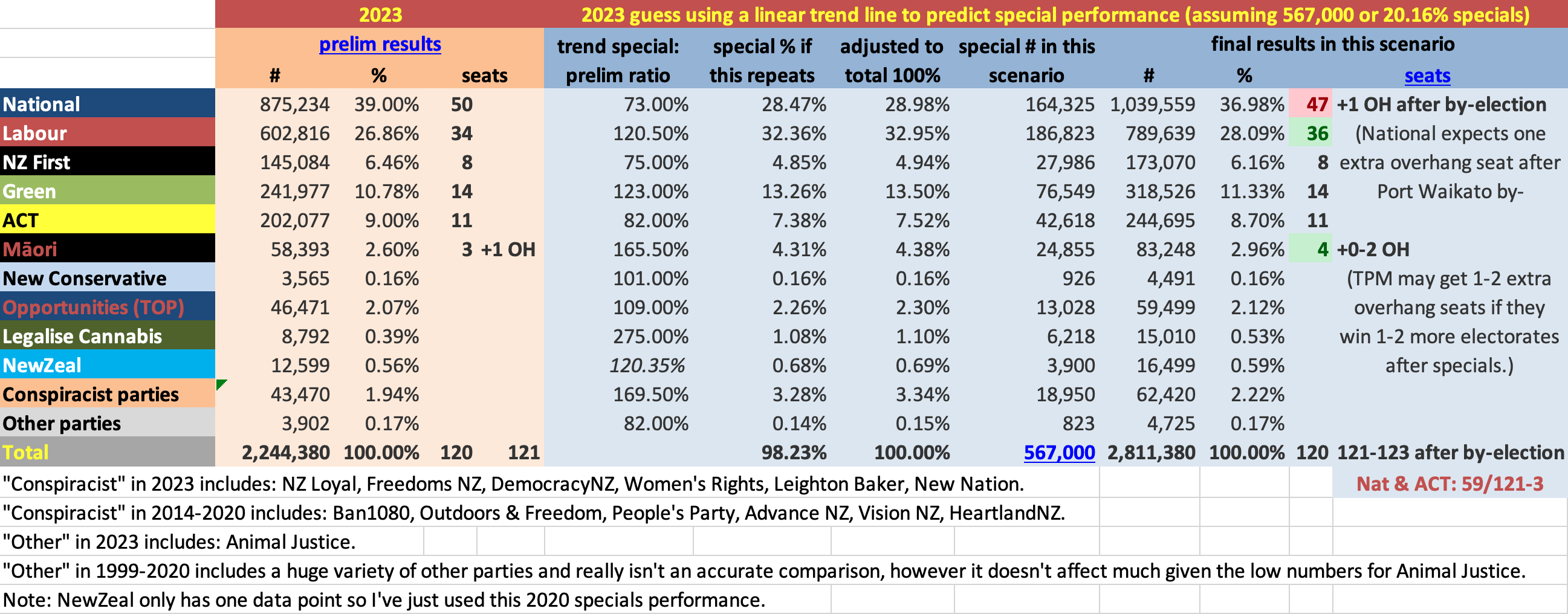

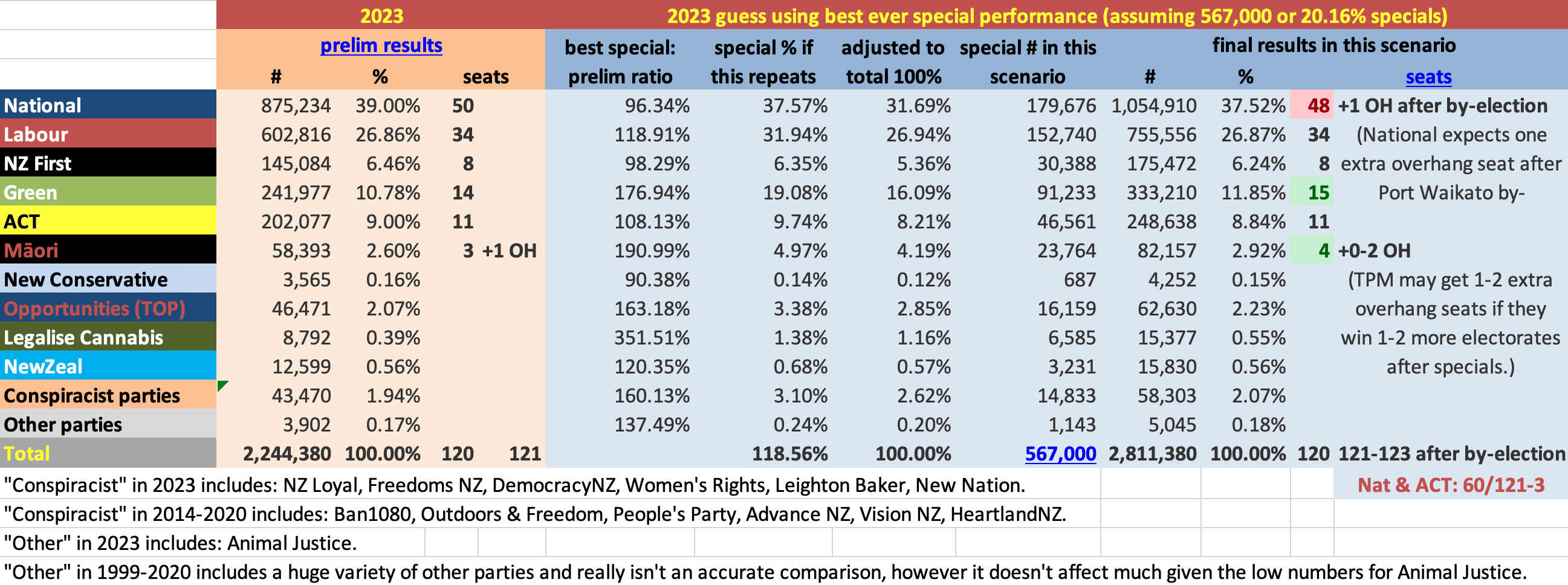

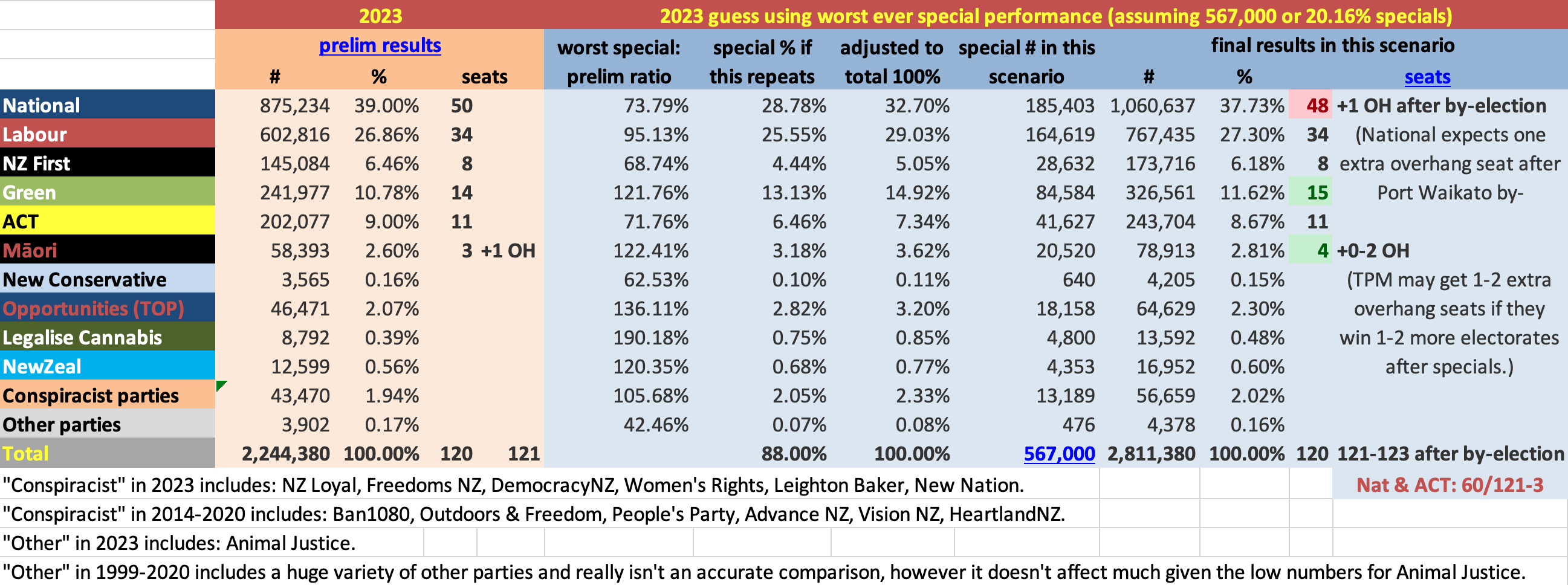

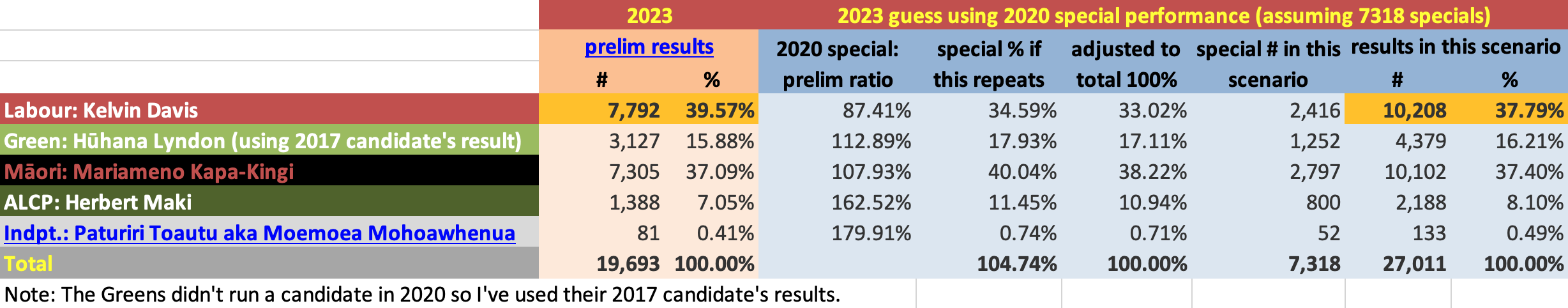

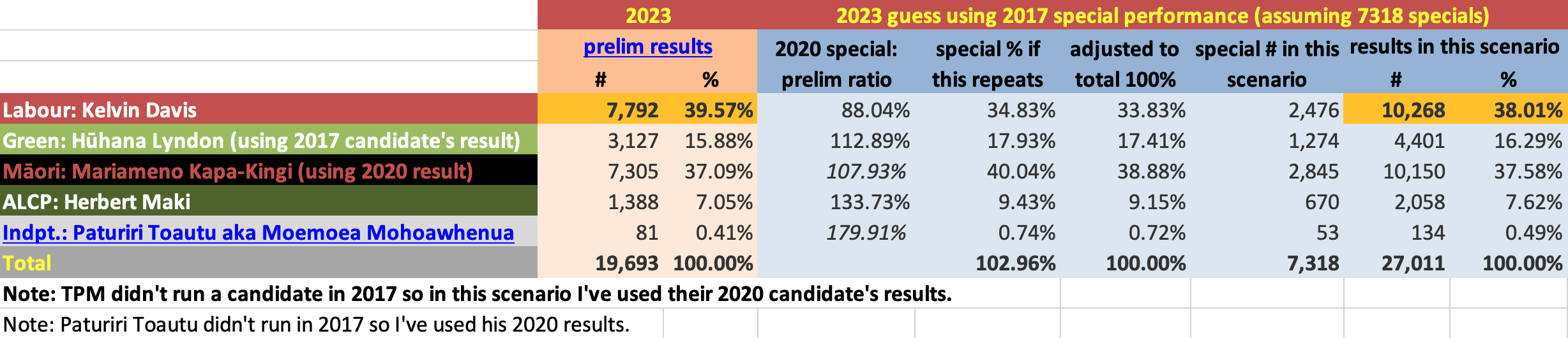

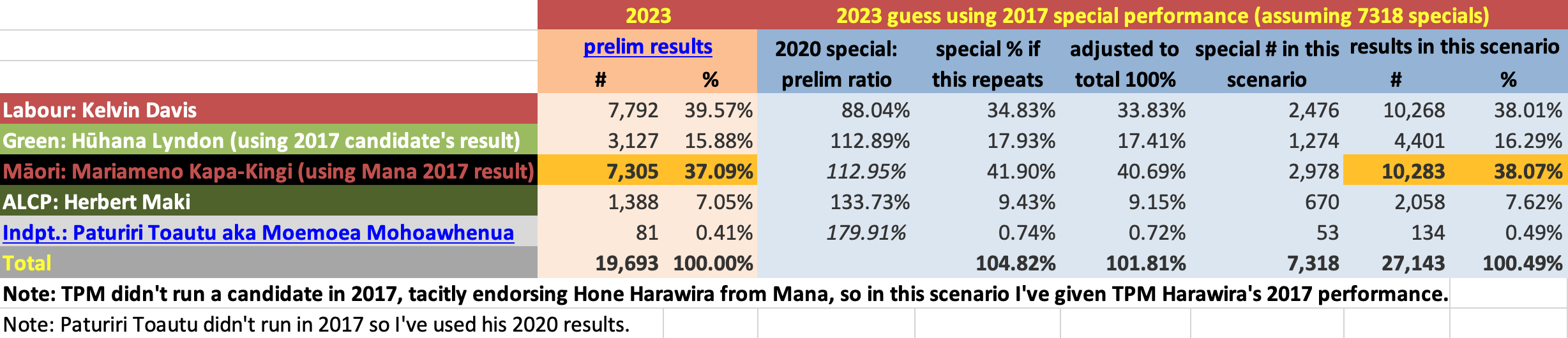

Here is how every party did, and then a comparison to other MMP elections…

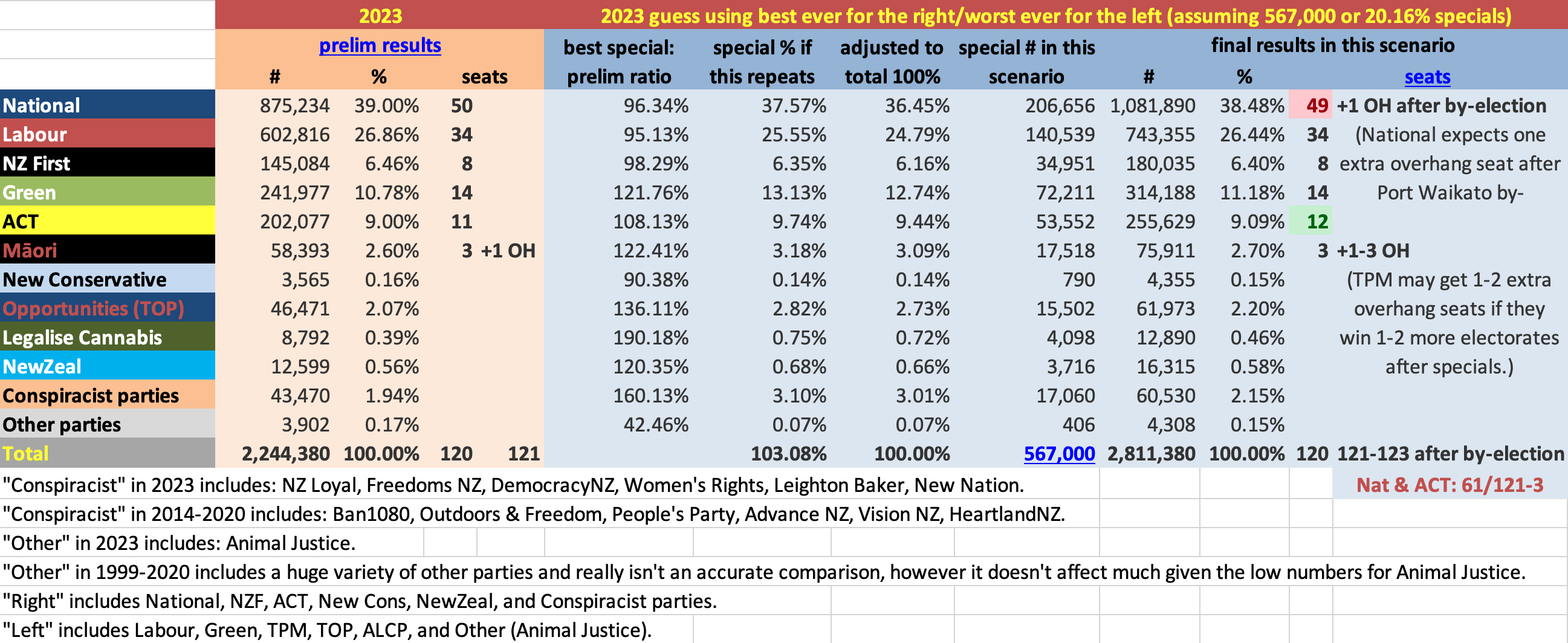

The other noteworthy factor was that National reversed their downward trajectory on special votes, getting their best performance on specials since 2008. However, they still dropped, as they always have. Even in a good year for them on specials, they still did badly enough to lose two seats from what they had been projected on preliminary results. National losing multiple seats on specials will be increasingly normal if the proportion of votes that are specials remains high or continues to grow.

Other parties did basically similar to how they’ve done before: TPM, Green, TOP, Legalise Cannabis, and conspiracist parties doing well on specials (though some not as well as before), ACT and NZF doing badly.

So, in summary, this led to the following changes in seat numbers from the party vote (with self-indulgent comments about how this compares to the predictions in my last blog):

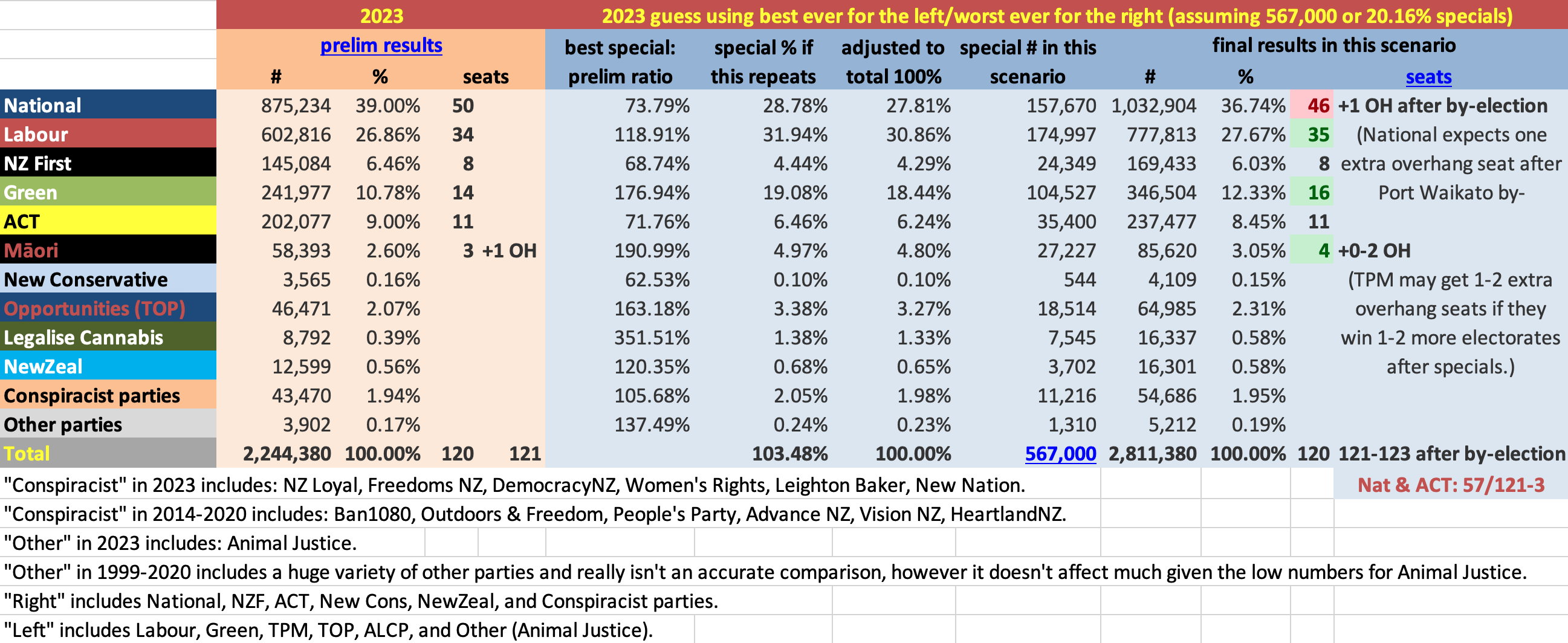

- Parliament will have 122 seats, with one more to come after the Port Waikato by-election. National + ACT will not be able to form a government on their own, as they will only have 59 seats (to grow to 60 after the by-election).

- In theory there are multiple possible governments, the first three of which avoid New Zealand First:

- Teal Deal: National + Green, 63 seats (to grow to 64)

- Grand Coalition: National + Labour, 82 seats (to be 83)

- Getting the Old Gang Back Together: National + ACT + TPM, 65 seats (to be 66)

- Winston Kingmakes the Left Again: Labour + Green + NZF + TPM, 63 seats.

- Three rightwing parties that dislike each other: National + ACT + NZ First, 67 seats (to be 68). In practice this is the government we will get, because all other combinations involve parties that have (explicitly or implicitly) ruled each other out.

- Labour did not pick up any seats on specials.

- This is contrary to most of my predictions.

- National lost 2 seats on specials.

- This is consistent with some of my predictions (though other predictions were that they would lose 3, which would have been nice but aah well).

- The Greens picked up one seat.

- This was predicted in most of my predictions. On some of my predictions they stayed on 14 and on others they went up to 16 but most said they’d go to 15.

- TPM picked up one more seat on party vote entitlement (however, since they won more electorates than party vote entitlement, this actually doesn’t affect their own number of seats in Parliament, just the overall size of Parliament, as discussed in probably excessive detail in the last blog).

- This was predicted in most of my predictions.

- No other party changed their seats from the preliminary predictions. ACT and NZF went down on specials as usual, but not enough to lose seats.

- This was predicted in basically all my predictions.

- There was one super hypothetical scenario on my predictions where ACT actually gained, but this coming to pass would require ACT to magically become good at specials again (and since they became a more-than-one-person party again in 2020, they’ve been bad at specials, just like the other medium-large right-wing parties are). NZF have been bad at specials for ages (retirees don’t do special votes). Realistically, ACT and NZF were definitely going to drop their vote on specials, not increase it.

How close were we to these seat numbers being different?

Changes in seats (or no change in seats) doesn’t necessarily clearly translate to change in votes, so generally it’s better to look at percentage changes in votes. Sometimes quite a small change in votes could push a party over the boundary to get one more or one fewer seats.

I’ve played around a bit, tweaking the the final numbers on the seats generator to see what kind of vote changes could have led to different seat numbers. Here are some ways that votes could have been different, leading to different seat numbers, in order of likelihood:

- If Labour had taken 0.2% of National’s total votes and 0.1% of the Greens’ votes, Labour would have won the extra seat instead of the Greens.

- If NZF had dropped 0.2% of their vote, to 5.88%, they would have gone down to 7 seats. That seat probably would have gone to National; could have been Labour, but only if almost all of these 0.2% votes went to Labour instead). But NZF still would have held the balance of power (National and ACT would have only had 61 out of 123 seats even after they get a bonus seat with the Port Waikato by-election).

- ACT had gone down from 12 to 11 in the last stages of the election day count, so they would have had a fair way further to descend for this to drop to 10. But even if it did, the votes & the seat would have realistically gone to National anyway, so wouldn’t have changed the overall size of the right bloc.

- While some scenarios had TPM staying on only 3 seats from party vote, realistically they would always have increased this to 4 as they always do so well on specials. Even if TPM had dropped 0.3% to 2.78% with (for example) 0.1% each going to Green, Labour, and National the seat numbers don’t change.

How special votes affected electorates

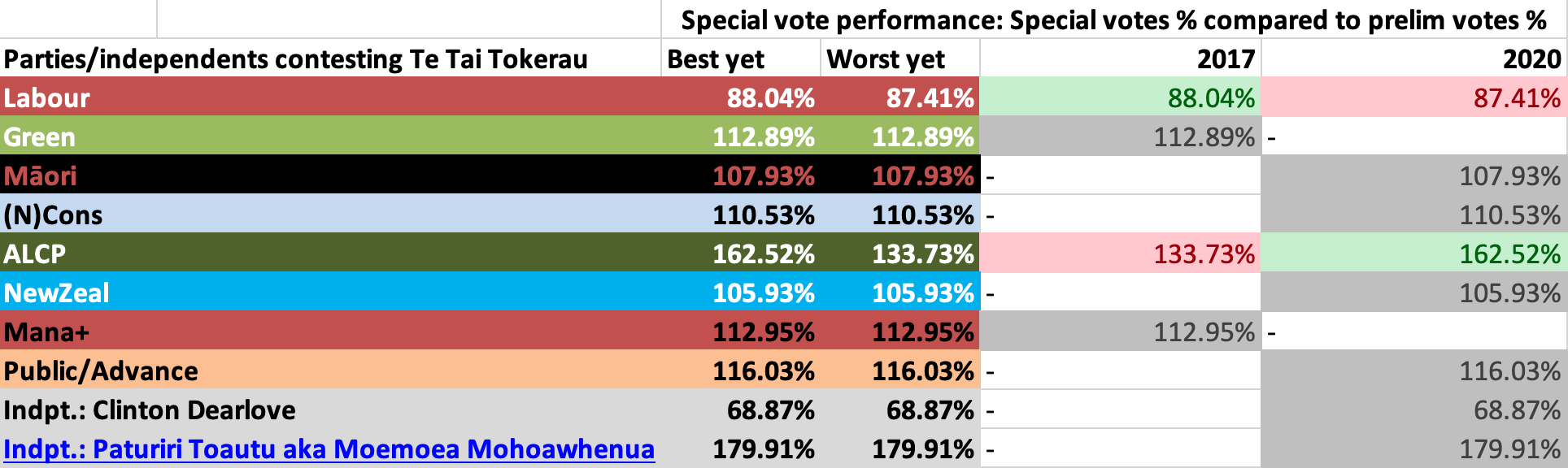

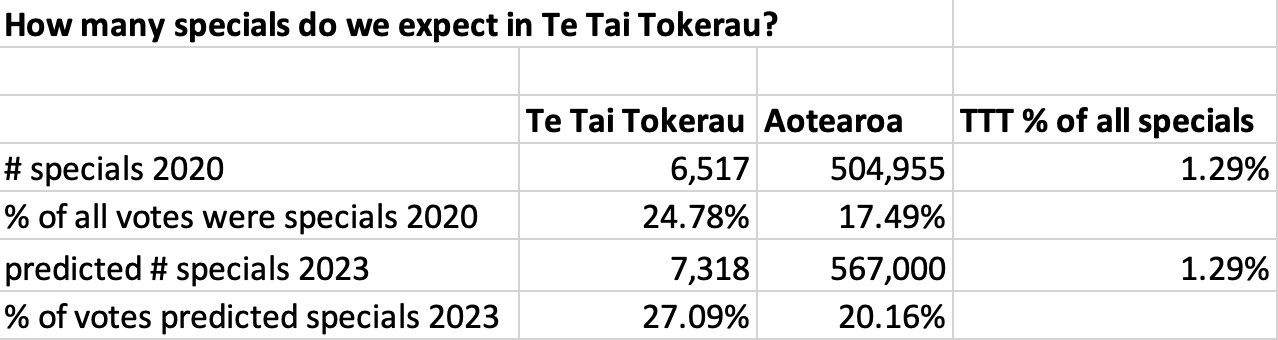

- Māori electorates: I said that Te Tai Tokerau and, likely, Tāmaki Makaurau were too close to call based on past special vote performances. 2017 and 2020 results ever-so-slightly favoured Labour’s Kelvin Davis to narrowly hold onto the seat, but with lots of uncertainty. (I lacked the data to do a projection for Tāmaki Makaurau.) It turned out Te Pāti Māori won both seats. In Te Tai Tokerau, TPM’s Mariameno Kapa-Kingi actually turned a 500 vote preliminary deficit into a 500 vote win by winning 3000 extra votes from specials to Labour’s Kelvin Davis’ 2000… big numbers considering Kapa-Kingi won with only 10,428 votes total. In Tāmaki Makaurau, the margin of victory for the TPM candidate is only four votes… yes, four single votes… so this will go to a recount and is essentially a tie. But TPM’s performance especially in TTT was likely helped by TPM delivering their normal excellent special votes performance while Labour failed on specials. Here are tables with the Te Tai Tokerau results this year and compared to 2017 and 2020.

- General electorates: I said in my last blog as a vague hunch that one or two seats would probably flip from National to Labour on the final count. In fact two did (Nelson and Te Atatū). I also added a more specific guess on the morning before final votes were announced when I saw a list of four seats identified as close (the Labour candidate just ahead in Mt Albert on preliminary votes and the National candidates just ahead in Nelson, Te Atatū and Banks Peninsula). My last minute guess was that Labour would win all four of these. I was right about three out of four but in Banks Peninsula, the National candidate actually extended their lead on the final count and won the seat by a relatively comfortable margin of 396 (after being 83 ahead on the prelim count).

Why the changes this time?

This is all entirely speculative.

I have three possible theories about why Labour did no better on specials than ordinary votes this time, and the first two of them would also be reasons why National did less bad on specials than they had been doing. There are not really any other significant changes to explain about other parties.

- A theory that some pundits were predicting was that overseas voters would abandon Labour because they were annoyed about the border closures and compulsory user-pays quarantine for people wanting to come home. This may explain some of it, even though overseas voters are only 78,030 or 12.9% of special votes. I will admit I have been sceptical about this theory, because I was an overseas voter who suffered a government that literally wanted to let the elderly die (and to a large extent succeeded in that), looking in at NZ’s best-in-world COVID policy and feeling more warm towards NZ Labour than I probably ever had before. Also, I had no intention to come back while MIQ was in place. However, I am willing to grant that the picture would have looked quite different to an overseas voter in Australia whose own government didn’t do too bad (relatively), who has always expected it would be relatively easy to pop back home, and who really wanted to come home in 2021 when a lot of other countries were giving up on COVID protections but Aotearoa wasn’t. So maybe there is truth to this pundits’ theory.

- Labour seemed to narrow the gap with National near the end of the electoral campaign when Hipkins finally had a good debate and National were going off the rails saying, basically, that the government with ACT and NZ First that they were (and are) set to form would be bad and that NZ First are racist but that they will work with them anyway, etc. Labour did somewhat better and National did somewhat worse on votes cast on the day than on advance votes (compare: advance ordinary votes with preliminary votes). So IF special votes are more likely to be advance votes, then this could explain why special votes were more National-leaning than Labour-leaning. BUT I don’t know if special votes are more likely to be advance votes or not. I’ve asked the Electoral Commission if this info is available (yes. I am a nerd.).

- A lot of special votes are students or people who move around a lot, who are staying outside the electorate in which they’re enrolled when the vote. A lot of others are first-time voters who enrol and vote on the same day. (I’m not sure if we have the data on how many of each group there are.) These groups are generally left-leaning and may have taken issue with Labour watering down climate commitments, not delivering on Ardern promising to prioritise it as “her generation’s nuclear free moment,” again ruling out any kind of wealth or capital gains tax, and failing to do anything about housing unaffordability. Ardern was a cautious centrist Labour leader, more timid than Helen Clark even after getting an unprecedented majority vote in 2020, and Hitchens pitched himself further right than that, offering no hope of any action on the major issues affecting the world and the future. Some of these voters may have gone back to the Greens or TPM (or voted Green or TPM in their first election instead of voting Labour). Perhaps similar to the demographics who (on both ordinary and special votes) abandoned Labour for Green or TPM in electorates like Rongotai, Wellington Central, and the Māori electorates.